Setting goals is hard, and it is even harder to reach them. As individuals, we struggle to do so, despite our efforts being directed to achieve a few things for ourselves.

As organizations, it becomes infinitely more complicated than this. There are goals ranging from corporate objectives to individual targets, with the intention to improve balance, sales, productivity, technology, and skills, among others. These goals are all expected to bring the organisation forward cohesively.

In every organization, you see the evidence of how hard this is, because members

- feel doubt about where they need to go to be successful or

- experience that the goals lead the organization in what they perceive to be the wrong direction, or

- experience that they can only influence goals very indirectly from their position, or

- find themselves in conflict with other parts of the organization, etc.

These examples all lead to hesitation that reduces the joined force of the organization. Imagine if we had a way to avoid this waste.

No surprise that frameworks for goal setting are in high demand. Latest OKR (Objectives and Key Results), which was popularized by Google1, has become popular, and organizations practice, typically at a team level, to formulate objectives and key results in the ‘right’ way.

Despite the origin and promises of success with OKRs, organizations often fail to achieve their goals, just as with all predecessors, such as SMART, Balanced Scorecard (BSC)2 with Key Performance Indicators (KPI), or any other fad of the time.

Why do we not achieve what we want with goal setting?

The answer is straightforward. It is just very hard in a large organization, and we underestimate the complexity of setting a direction for thousand(s) of people to achieve the synergies from their work.

No goal-setting framework can remove this complexity. At most, it can set some structure to the process and the goals. There is no ‘silver bullet’ – despite what you’re promised.

This article is not a ‘silver bullet’, either, but an attempt to dive into the essence of goal setting to help organizations understand what it takes to be successful in goal setting, which includes:

- reminding you of the multiple reasons why we set goals, because that uncovers what we need from goals to be successful

- highlighting the attributes that every goal needs to live up to – one being how to measure progress

- making you aware that goals are very contextual and illustrating those differences

- showing how alignment top-down and across the organization can be done, and

- how to maintain the goals over time

I’ve succeeded if you end up knowing how you use goals to optimize the value created by your organization, and that it takes somewhat more than being able to spell, e.g., OKR.

If you think you already know, I’ll challenge you to read anyway and then test your current goals with the attributes and the alignment presented here. I have met many leaders who were satisfied with their goals, but I have yet to meet a set of goals that passes the test. If you do, please get in touch – I would love to learn more about how you do it.

Why do we set goals for the organization?

The question seems so trivial that it’s not worth answering, but it’s not.

In many organizations, we’ve repeated the yearly strategy ceremony, because we had to, rather than being conscious about how it can be essential to create value for the following year.

Already the father of formalized goal-setting in organizations, Peter Drucker3, wrote Management By Objectives (MBO) in 1954, what outcome we should aim to get from our goal setting initiatives:

- set the direction for the organization and its members

- motivate people for action

- support decentralized decision-making to increase speed and maneuverability

- align across the organization to achieve benefits and avoid dependencies

Each one is hard to achieve in itself, and all at once, even more. Let’s start by taking a closer look at each one.

Set the direction

Any good strategy4 should have a diagnosis, a guiding policy, and a set of coherent actions, according to strategy guru Richard Rumelt. I’ve written about the first two previously5, and among other ideas, I’ve highlighted my preference for visual artefacts like Business Model Canvas and Blue Ocean Strategy canvas as great expressions for both context (market, user, tech, …) and intent.

Actions to implement a strategy can be formulated in various ways, but nowadays, due to the influence of Peter Drucker, they are primarily formulated as goals.

The goals are a concrete, yet condensed representation of the corporate strategy, interpreted locally, where you are. Of all possible initiatives, they capture the few that are prioritized. They serve two purposes: to guide the local part of the organization and to inform the rest of the organization about what it can expect from you, and implicitly, what it cannot expect.

In the remainder of the article, I assume that thorough strategic analyses have been performed prior to goal-setting, as suggested by Rumelt, and decisions on where to focus, i.e., the direction of the goals, have been made. To me, strategizing is not only done at the top of the organization, but it must also be done locally to ensure goals are relevant for those who are expected to meet them. More about this later.

Motivate for action

Let’s begin with the elephant in the room: bonuses. Although much research has shown that extrinsic motivation has no positive influence on knowledge work—somewhat the contrary6— still a lot of organizations set goals to determine performance-related pay.

Despite the lack of effect of bonuses in themselves, well-formed goals can motivate as they show progress. Internal motivation, stemming from knowing that you’re doing well, remains motivating.

Reward structures can be among the hardest structures to change in an organization, so if you want to set better goals, you might as well utilize that existing structure to achieve the following reasons to set goals.

Support decentralized decision-making to increase speed and maneuverability.

More than 70 years ago, Drucker understood that empowering the organization was necessary to be able to compete, and that need hasn’t decreased since.

If the set of goals you work to achieve is negotiated seriously with your superiors and other stakeholders, they can/will constitute guardrails for decision-making in your area. They will provide local autonomy, ensuring speed and quality in decisions. You are not hindered while waiting for escalations and are empowered to make decisions that best fit your local opportunities.

Suppose you’re heading a part of the organization. In that case, the set of goals that you negotiate with your subordinates will be the contract that you can expect them to achieve until re-negotiation.

Alignment across the organization

Just like goals can create transparency around accountabilities top-down within the organization, they are well-suited for alignment across, i.e., ensuring that if objectives are shared among groups in the organization, everyone is aware of the dependencies and can coordinate accordingly.

If this transparency does not exist, there is a big chance that goals will be missed.

You probably already think that for goals to deliver on the above, they must be of high quality and based on serious strategic work. You’re right. If you do not think there’s time for this in your organization, then imagine the pain ill-formed, irrelevant, conflicting, etc., goals cause to your organization. A pain that you, as a leader, must use your valuable time to resolve …. and then perhaps not have time for setting better goals !

In the following, I would like to delve deeper into goals as a source of motivation.

Goals must be more than SMART.

Georg Doron7 introduced the acronym S.M.A.R.T. in 1981, which builds upon MBO. Despite 45 years of evolution in the use of goals, it remains applicable today. In my opinion, every goal-setting framework should at least comply with these guidelines. However, I’ve seen many, if not most, organizations struggling with these five basic rules of thumb when setting their goals.

Therefore, I’ll briefly review them before explaining their implications for teams in various parts of the organization, and how they are interconnected both top-down and across.

Specific and measurable

Specific and measurable means that every goal should be clear, unambiguous, and trackable towards progress and success. It sounds much simpler than it is. Take, for example, this goal:

Implement a new organization for …. this year

It is very ambiguous because any minor change to the organization would qualify, so whoever is in charge can claim success. Furthermore, it is binary: it is either done or not; there is no measurable progress while trying to achieve the goal. You probably recognize this kind of goal when it comes to finishing projects, implementing processes, or technologies, etc.

This goal is furthermore not specific about the direction and therefore probably not something you’ll completely delegate, which is one part of what we want to achieve by setting goals.

To achieve what we want from goals, they need to be leading, i.e., you can continuously monitor progress in near real time. That means metrics that are only calculated quarterly or in other ways delayed are not well-suited for goals. If possible, goals should be measured automatically, not only to obtain real-time data, but also because it removes the ambiguity of human- or self-assessment.

I’ll get back to how to formulate measurable leading goals shortly.

Achievable or attainable

Achievable/attainable means that the goals are possible to meet, and again, it sounds simple and obvious, but it’s not. It is actually an essential discussion whether a goal should be achievable or attainable. The two words resemble the difference in meaning of what output you deliver versus the outcome you create for someone.

The big difference between the two is whether you aim to deliver the output as planned or if you’re not done until the outcome is attained. If output alone is the focus, there is a risk that the organization as a whole does not benefit from your efforts.

Another relevant question is whether a goal should be realistic or a stretch.

Many organizations favor predictability and have implemented reward structures that reward achieving goals 100%. They interpret a goal as a commitment, and hence, people are careful not to overcommit. Google avoids this. Be defining 60-70% as a success. As may be apparent already, I favor continuous measurements, because it gives a times series/graph that shows progress over time and can be input to interpretation and decisions about continuing or giving up on a goal.

Despite the approach, the goal must be expressed in a way that clearly defines the criterion, and preferably, as mentioned above, in a manner that allows progress to be tracked over time.

Relevant

I consider a goal relevant if

- it contributes to organizational goals,

- is the result of prioritization through strategizing, and

- can be directly influenced by those who are measured by it.

These are actually three unrelated attributes for a goal, and in my experience, it takes effort to create goals that comply with all three.

Organizational goals are often financial, e.g., revenue, sales numbers, etc.. If you’re on a development team contributing with other teams to a larger product, your influence on revenue is at best indirect and unmeasurable. If revenue increases, how can you be sure that it was your contribution that persuaded the customer? If you work in a support function (aka staff/administrative/corporate function) offering your services to fellow employees, it is even harder to track the connection. Nonetheless, it is essential for stakeholders’ insight, internal motivation, and learning to have transparency.

As mentioned, I encourage some degree of strategizing everywhere goals are set, because local insight and ideation very much ensure relevant goals. This aligns with Google’s rule of thumb that 60% of OKRs should be formulated bottom-up to ensure motivation.

I’ll address how relevance can be achieved for all teams later, as the concrete goals are highly contextual.

Time-bound

Time-bound refers primarily to the date by which the goal should be achieved/attained. In most organizations, goals follow a planning cadence, either yearly or quarterly, and are also tied to the reward system. Here it is in one’s own interest that goals are low in ambition, entirely within one’s control, and long-lasting—the opposite of a stretch.

However, from an organizational perspective, that is counterproductive. You’ll want to invest the minimum necessary to achieve the desired outcome, or stop as soon as you can detect that the outcome cannot be achieved with a reasonable investment. Optimum is rarely to stop when you’ve delivered the output, or time expires.

Eric Ries8 introduced the concept of innovation accounting, which captures exactly this: if you continuously measure progress toward your goal, you can decide whether to persevere or pivot while investing.

Any strategy, including the goals it sets, should strive to achieve maximum value for the investment; therefore, you should aim for innovation accounting for your goals, i.e., the planning cadence will rarely fit the time period of the goal. Goals will be reached within the cadence, or will be updated when entering a new planning period.

S.M.A.R.T.

In summary, if you want your goals to be motivating, directing, delegating, and aligning, there are a few rules of thumb you need to follow:

Focus the goal towards the outcome you want to attain. That’s the explicit formulation of the relevance, and when measuring, you can better decide whether it’s time to stop or continue further to attain more outcomes.

Ensure that the goal has an undelayed, continuously developing metric. That ensures immediate and ongoing motivation, and it supports decentralized decision-making because it is transparent to the organization, allowing for timely decisions to be made.

The goal should be an outcome that the people responsible can directly influence. Do not pretend that, for example, your HR department can directly affect the sales numbers. Relevant goals for them should be the outcomes they create for their colleagues, who can increase sales. Encourage local strategizing since that helps to ensure people find goals relevant.

The most effective way to achieve these three ambitions is to formulate goals with outcomes that focus on the specific user and the behavioral change we enable them to achieve. In the next chapter, I will translate these rules to concrete examples for different parts of the organization.

Finally, the goals should be aligned both top-down and across the organization to ensure their corporate relevance and that the goals across the organization add up rather than conflict. I’ll elaborate on how to do this in the chapter after next.

Differences between goals

In many organizations, strategizing has been something reserved for a select few at the top of the organization, with the strategy cascading downwards to the rest of the organization for a year at a time. More and more organizations, however, realize that strategy and, hence, goal-setting must be continuous because business conditions, technological opportunities, compliance demands, and other factors often change. Furthermore, each area in the organization is too complex for someone with limited or outdated insight to set goals that are sufficiently detailed to be both directive, relevant, and empowering for areas within the organization.

As I mentioned earlier, the concrete formulation of a great goal depends on the context of the area within the organization. In the following, I’ll make that somewhat more concrete, well knowing that responsibilities are shared differently in different organizations and, of course, are much more complex than these examples, so bear with me:

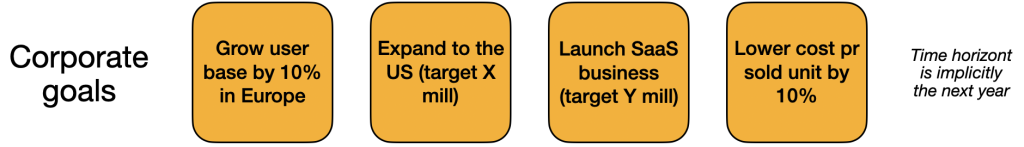

Corporate

The organization has a raison d’être: possibly a mission in the world, combined with some financial targets set with the board of directors: revenue, profit, growth, etc. Below are a few examples of corporate goals: growth in existing markets, expansion into new markets, a change in business model (SaaS = software as a service), and cost reductions.

The goals are typically based on the accounts and hence lagging and not measured continuously, except for the first example, where it could be counted every time a new user uses the product. This, however, introduces uncertainty regarding the financial numbers, as it assumes that the 10% new users are as profitable as the existing users.

Since financial goals are far from enough to direct, delegate, and align the organization, it has become popular to combine these with Big Hairy Audacious Goals (BHAG)9 or Wildly Important Goals (WIG)10 or whatever they are called in your organization.

As their names indicate, they only set direction for the most critical initiatives in the organization – so few that it is easy for the C-level to control, but far from enough to direct the efforts and empower the whole organization in a relevant way.

In the examples, I have deliberately refrained from using any of the mentioned methods, since I aim to make everything I write independent of preferred goal templates. You can replace formulations with OKRs of whatever you prefer.

Notice that the C-level directly influences none of the goals but rather achieves them through aligned efforts in the rest of the organization. Therefore, the areas in the organization must be involved in strategizing to set the direction for their work.

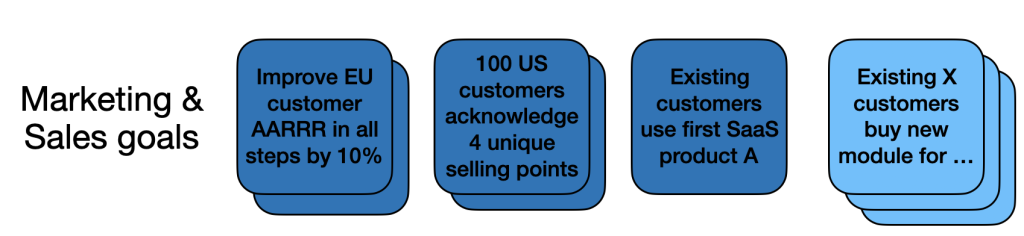

Marketing and sales (MS)

Strategizing locally within Marketing and Sales (MS) should, of course, be loyal to corporate goals, but it should consider all products, all markets, customer segments, expansions, etc. MS employees have unique insights from meeting with customers at an intimate level that the C-level will never have.

Due to the tight connection to corporate goals, strategizing in MS often tends to lead to financial goals as well, but to set clearer direction for the efforts, the goals should be leading, measurable and directly influencable as recommended: Set goals that focus on the user, in this case, the one who purchase your product and the behavior wished from them during the sales pipeline/process.

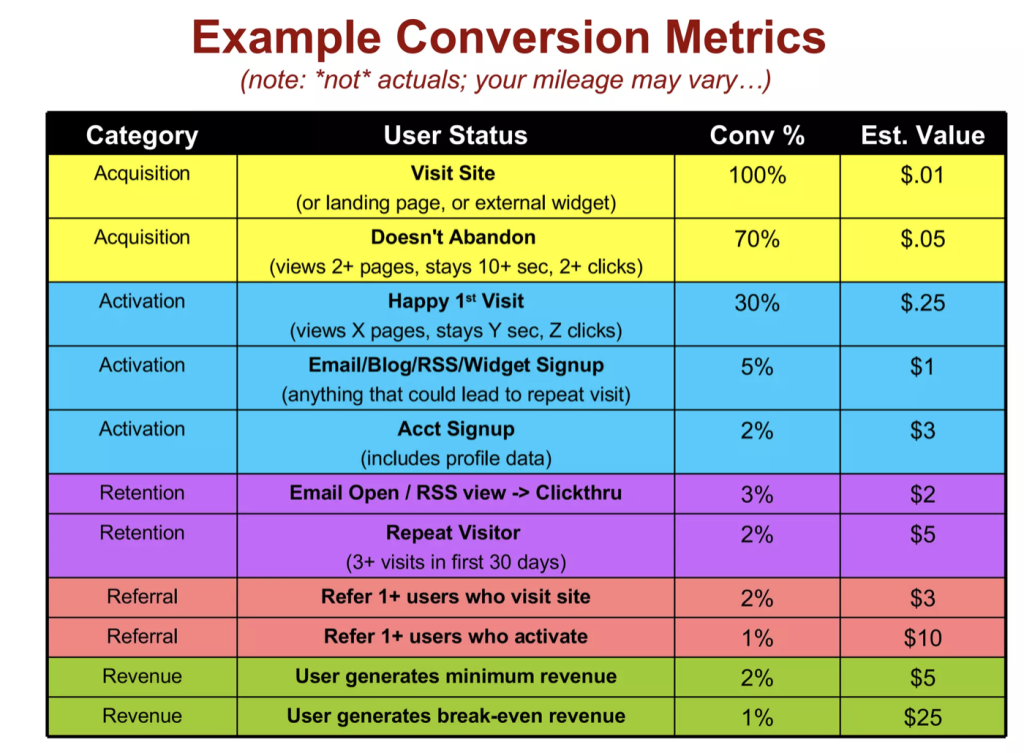

Let’s look at the outcome that MS creates in the purchasing process. For B2C customers, the Pirate Metrics Framework11 (figure below) provides leading metrics that can guide MS employees in making decentralized decisions that influence those metrics.

These metrics are typically measurable in a software product, and therefore, MS will have continuous feedback on their efforts. Initially, the relationship between the AARRR metrics and actual revenue is purely assumption-based, but tracking them over time will create insight into the effect of your MS investments.

Many B2B products are sold through a highly manual process, but it is still beneficial to adopt a similar mindset. Do not just measure actual sales, but also track the entire sales process, such as in a CRM system. It requires more discipline from employees to maintain accurate information about each activity. Therefore, the measurements must be designed to benefit them, allowing them to continuously track their progress toward goals, identify the influences on their sales process, and improve each step.

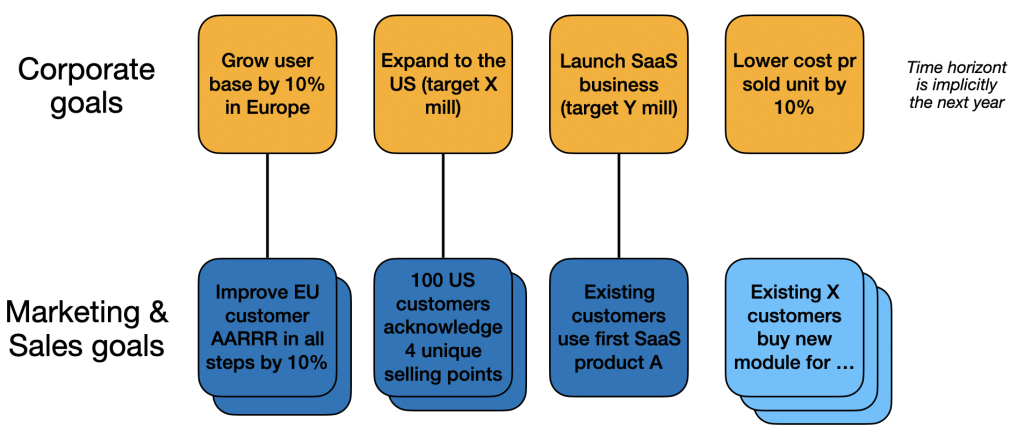

In the example below, AARR is used for goals towards the existing EU market. It could also be used for the new US market; however, they also want to know specifically if they succeed in communicating the uniqueness of the products. The third goal is designed to capture customers who think that a SaaS solution is relevant, and to turn existing customers into happy references for further sales, rather than generating revenue. Finally, MS, of course, has identified other opportunities outside corporate strategy; in this example, they’ve identified opportunities for a new module they believe will be able to sell to existing customers.

In many B2B sales, customers request specific developments in the products they are purchasing. Therefore, it’s essential that MS has transparency into the goals of product development and can influence the priorities.

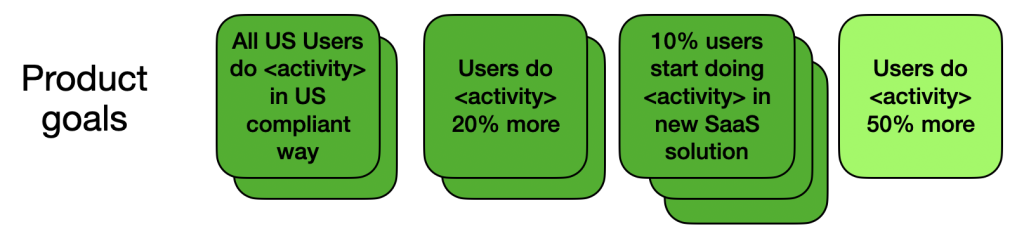

Product development (PD)

Strategizing for product development (PD) is based on input from corporate and sales strategies, as well as PD’s understanding og their users, competitors, technology, and other factors, and involves choosing the most valuable development for the products.

The organization may have multiple products or a complex product that requires several product teams12 to work on different parts of the large product. It makes sense to obtain the benefits of setting goals by asking every team to strategize. That, of course, results in many more goals in total, but they are aimed to provide direction for local decision-making, not, for example, for the C-level to track everything.

The outcome of PD is never revenue, etc., directly because the delay from deciding to build something, building it, and selling it until it ends up on the quarterly accounts is long, and typically, it’s lots of other things that happened in that period that affect the result. So developers cannot know the outcome of their specific contribution.

The best way to formulate outcomes in PD is, as mentioned, the behavior changes that development teams create in users. Truly Agile teams can implement measurement of user behavior and track it from before they start making the desired changes to the user behavior until their desired outcome is achieved, or it shows that the outcome cannot be achieved for a reasonable investment.

In the example above, all goals are formulated as user outcomes and look quite simple. Still, as mentioned, the number will be significant in organizations with a complex product and many teams. In that case, you may have higher-level product goals, for example, if US compliance requires several users to perform an action across the entire value stream of a product, which could be captured as the number of completions of the whole value stream. To delve into the depth of this will require a more specific example, and there isn’t room for that here.

Depending on the development team structure, a development team may rely on other teams to deliver the outcome. For your goals to be as effective as possible, you should limit these dependencies; however, they will exist and should be transparent.

Support teams

Where PD supports users of the product, support teams support users within the organization. For example, platform teams support productivity in PD by providing efficient and quality platforms and processes. The HR team supports, for example, better recruitment, Legal support contracts, and compliance in the organization. These teams, of course, also bring the goals of their users into their own strategizing process, where they, with a lot of other input, decide on their future goals.

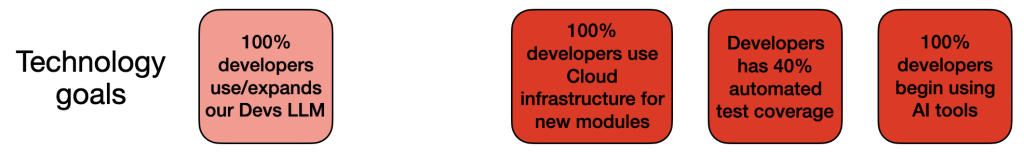

For support teams, it’s equally important to focus on outcomes for their users, i.e., colleagues, and have the leading measurement of user progress, just like the product development teams. The example above is from technology support, where they are supporting developer behavior by providing new infrastructure, tools, and technologies required. Another (Large Language Model) is a new opportunity that they aim to give PD. Notice that the goals are not what the support team delivers, but their user change to the desired behavior.

To make it clear: Support teams do not need to be organizational units – cross cutting concerns can be liftet for example by Communities of Practice. Goal setting for these is similar to the above, so I’ll refer any curiosity about alternative organization to previous writings13.

Individual goals

Many goal-setting frameworks emphasize the use of individual goals and hence (in-)directly performance reviews. There is no reason why the above won’t apply to individuals, but I won’t go into that here. My beliefs are that true organizational value originates from teams, and alignment within teams and between teams is the hard part of moving an organization in a common direction. That is the topic of the remainder og the article.

Summary

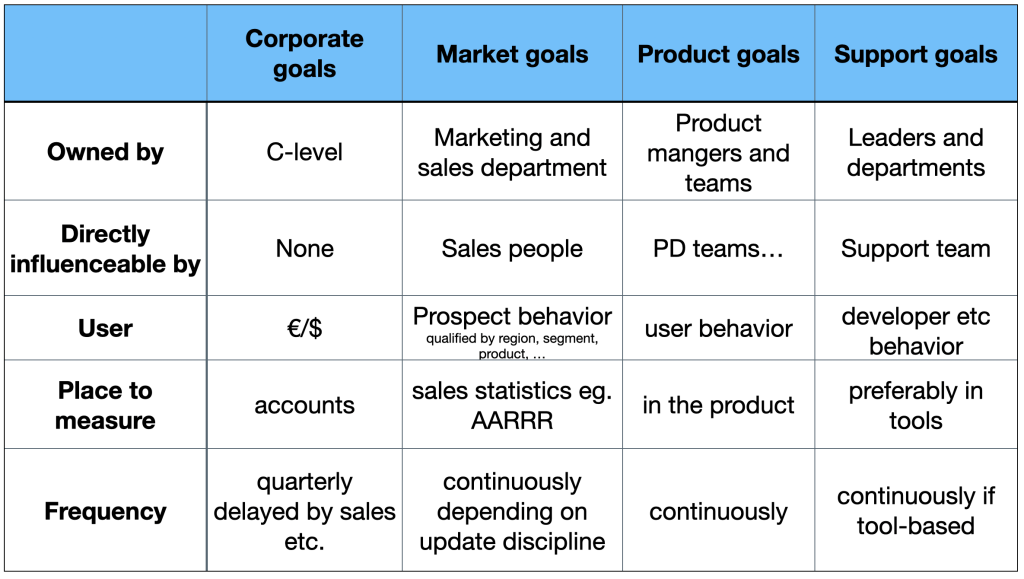

Below are the characteristics for each goal type, including ownership, who influences, users, measurements, and frequency, which must be known for goals to work locally, directing, motivating, and aligning.

All focus on user behavior change and continuous measurement wherever possible.

Aligning goals in the organization

So far, I’ve concentrated on what makes great goals, regardless of what goal-setting framework you use.

I’ve mentioned that these goals can neither be formulated directly from corporate goals nor independently of each other. It is obvious that if parts of an organization are moving in different self-interpreted directions, it will cause tension to a degree that it prevents progress. I am sure that everybody has experienced counterproductive actions within their organization: sometimes as a consequence of power struggles, sometimes because of competing interests of goals, for example, between business ambitions and technical platform decisions, sometimes due to the lack of (transparency to) goals, and sometimes due to a lack of ability to adapt to each other.

The overall ambition must therefore be that the whole organization moves in the same direction, and the ambition of this chapter is to explain the alignment needed to obtain that. As mentioned, conditions for most organizations are volatile, and hence, strategizing is a process that runs quite often, and every time, a little or more realignment is needed. I’ll therefore go through three types of alignment:

- Establish the cross-organizational alignment, e.g., the first time or when the corporate strategy changes significantly.

- Continuous alignment along dependencies between teams

- Aligning different parts of the organization at a fixed cadence to allow for larger re-prioritizations between teams

The cross-organizational alignment based on relevant local strategizing and goal-setting is quite different from a top-down process, because although they are founded in corporate strategy, they are both dependent and also inspire each other to go in different directions. Even to adjust the corporate strategy. The illustration to the right originates from my previous writings14.

In the following, I’ll go through some of the dynamics that’ll lead to an aligned map of goals, which directs the organization towards a common goal while still being locally motivating and empowering.

Corporate strategy

Of course, corporate strategy and goals are the outset for all alignment in the organization. Still, as argued above, it is rarely sufficient to set the most relevant goals for the entire organization.

Even though these overall goals are typically negotiated with the next layer of management, they leave a significant space for interpretation for most of the organization; therefore, alignment is necessary.

You have probably noticed that I’ve avoided writing that goals cascade downwards in the organization as the way to align. This is very deliberate for several reasons:

- As described before, relevant goals are not of the same ‘currency’ as you move around the organization, and if you try to take a €/$-corporate goal and divide the amount pr behavior change, the relevance suffers

- Some corporate goals are inspired by goals from below

- Some lower-level goals are not directly connected to the corporate goals despite high relevance

However the following exercise is about revealing the assumptions behind the connections between goals at different levels. Following the connecting lines, you can make your opinion if for example a sales goal can be attained based on the prioritized improvements in the product from different development teams. This will be much clearer in the following.

Aligning goals in Marketing & Sales

As mentioned, the goals of the MS department should reflect the corporate goals, as well as the options they consider the best for increasing sales. If the corporate goals are high-level, it is their job to make them specific enough to measure the effect of their actions on customers.

The example used above (repeated below) illustrates (in blue) the best bets from MS, many of which follow directly from the direction set by corporate goals. Notice I only provide one concrete example pr goals, but indicate that typically you’ll have multiple. Additionally, other ideas are also highlighted (lighter blue). With a connecting line, it is shown that it is assumed to fulfill the corporate goals. The unconnected are the goal(s) that are believed to have great potential. The sum of them is aligned within MS to be attainable within the time horizon with the measures at hand.

There needs to be a dialogue about whether the achievement of the MS goals is sufficient to fulfill the corporate goals. If not, the goals are not aligned, and either MS must strategize further to identify additional actions to take or corporate goals may also need to be adjusted. Corporate goals may also be expanded with the opportunities identified in the MS strategizing process, but not necessarily, since MS may be empowered to pursue its own goals.

When alignment is achieved, MS needs to validate that it can actually deliver on this promise. Remember that they are continuously measured on progress. They may not have the capacity to meet with as many customers as they predict is necessary. Then they need to realign again to either reduce targets or grow capacity.

To achieve their goals, they may also depend on product development (PD) to extend the product, with specific outcomes for the US market, or deliver the product in a new way (software-as-a-service). Again, dialogue – this time with teams in product development- is needed to ensure alignment and attainable goals.

Aligning Goals in Product Development

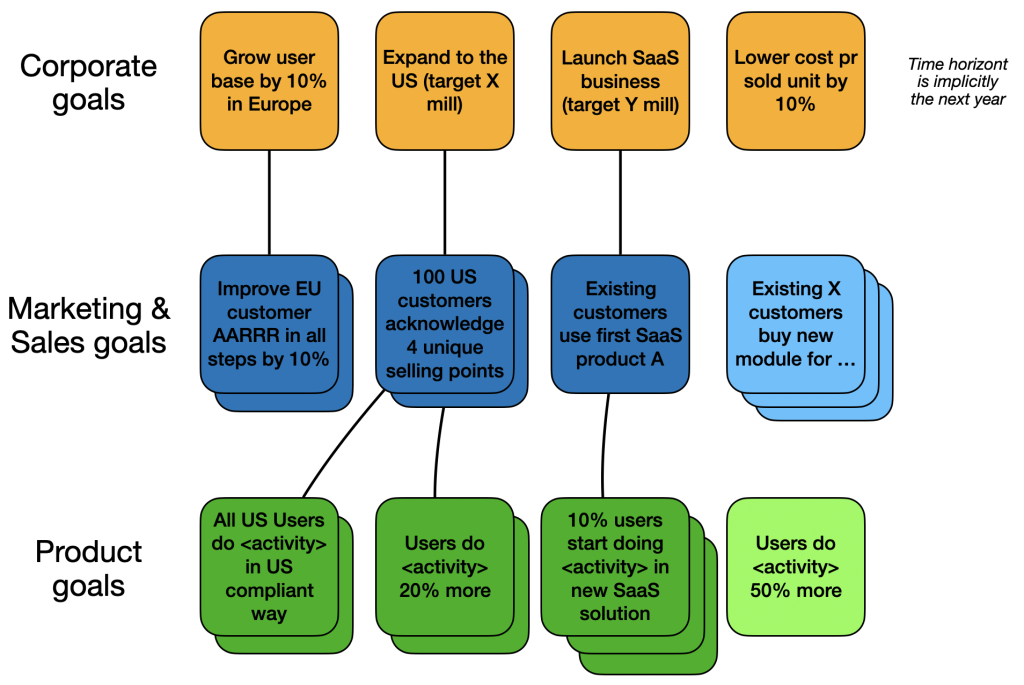

In the figure below, it is shown with dependency connections what changes from PD that are assumed to be attained for MS to be successful in achieving their goals. Most goals probably originate from the local PD strategizing process and are mapped backward to MS/corporate goals, and some may be derived directly from MS goals.

If PD cannot commit immediately to MS due to capacity constraints, then the alignment needs to be broadened. To preserve the internal alignment around attainability, PD can either:

- postpone their own strategic roadmap (light green)

- reprioritize the commitments they have to other stakeholders, or

- they can together prioritize the outcomes that contribute to the MS goal, or

- ask for more capacity

I have no general recommendation on which of the four is better, despite a top-down strategy process that would point to the first. Alignment means that stakeholders lean towards each other and understand the difference in perspective, and find the best overall solution.

PD may, in their strategizing, have identified product opportunities that they assume have more potential than corporate or MS strategies, and, of course, these should be prioritized in the alignment process. Consequently, that may require new goals in MS or even on the corporate level.

What is not illustrated in the example is that there might be dependencies across PD between sub-products, because they are released together, etc. These dependencies also need to be aligned to reflect what PD can be trusted to achieve in its entirety. Without going much deeper, these dependencies typically also require that the two parties measure their combined effort to preserve the same transparency that single goals have.

Aligning goals in Support

The alignment between MS and PD might also include tech teams in case new technology is needed – in this example (see figure below), the entrance into the SaaS market requires a new infrastructure and hence goals, timing, etc., need to be aligned between PD and Tech.

Any support team, of course, primarily supports the product team’s ability to create outcomes for their users. That may enable higher efficiency, either as a goal in corporate strategy (the last goal in this example) or as a request from development teams as a whole.

Support teams typically also have their own strategizing process, which results in the exploration of new ways of working, new technologies, and so on. In my experience, however, when prioritizing business opportunities against opportunities and challenges chosen by support teams, support often ends up losing. Therefore, aim to align MS, PD, and Support strategies with respect to both short-term and long-term time horizons, so the organization is not caught unprepared, like in the example where the cloud infrastructure was not ready when needed.

The aligned Goal Map

The result of this (first) alignment process is an entire Goal Map displaying goals from every part of the organization and the connections between them. Every part is aligned internally, i.e., they believe that they can attain their own goals, and they have aligned along dependency lines to ensure that they can trust their colleagues to get what they need.

When we’ve carefully ensured that a leading measure accompanies each goal, there is complete transparency on progress, which makes the alignment map a powerful artifact enabling everyone to act when their assumptions seem to be slipping.

Continuous alignment

Based on the transparency provided by the aligned Goal Map, every part of the organization is obligated to continuously align along the connection lines whenever they adjust their own goals due to unforeseen events or suddenly appearing opportunities, or they identify that the goals they depend upon are slipping. Working with others involves their responsibility to keep the map up-to-date.

As time passes, bilateral adjustments accumulate, and local strategizing may necessitate larger re-adjustments. Therefore, it is necessary to convene among several stakeholders to accommodate broader changes.

For example, MS might land a big sale that depends on product improvements, which they then want PD to prioritize higher compared to the already decided strategic product roadmap. Repriorizations mean that some connections on the Goal Map will be removed, and hence other parts of the organization will not reach their goals.

The more short-term repriorization that happens, the more goals suffer, and against intentions, strategic work becomes less relevant, the motivation to be strategic deteriorates, and the clarity of direction of the organization decreases.

Major changes should preferably be accumulated to be handled at an agreed time, e.g., on a fixed cadence.

Alignment cadences

When you have an agreed cadence, let’s say quarterly, you’ll also adapt the planning horizon to it with a larger focus on delivering in the current quarter, while later quarters are more intentional, since you’ve agreed to be able to renegotiate dependencies.

With local decentralized decision-making being continuous alignment with peers, the alignment cadences typically consist of events for larger parts of the organization. For example, product managers meet to align a new version of the collective roadmap with each other and identify if they need to have a round with support teams. Before the event, the PMs should reiterate their strategy, including new market input from MS. Then, discussions among the PMs at the event, and ending the event by sharing the new roadmap with MS, so that they can adjust their sales messages.

Another example is the support teams holding events where they inspire, e.g., PD, with new opportunities. The intention is to identify which technologies, etc., they should start preparing and which there is no appetite for, and then update their goals.

A third example is when several (sub-)products in PD have to work together to deliver on an extensive program. I have described a concrete example in another article15.

Finally, the obvious example is the (yearly) update of the corporate strategy, which enforces alignment across the entire organization. This does not have to be like the initial alignment exercise described above. If top management focus on the changes compared to last year, the process can concentrate on adapting existing local strategies and goals, thereby saving a significant amount of replanning.

Adopting this approach strategy moves away from a yearly top-down cascading process to several more dynamic iterative processes that continuously adapt current goals to the learnings made in the organization. A process where every part of the organization is responsible for and empowered to make the most value for themselves in alignment with the rest of the organization.

This way, we improve the chances of meeting our ambitions for setting goals:

- set the direction

- motivate for action

- support decentralized decision-making

- align across the organization

Summary

In this article, I have tried to get behind and beyond traditional goal-setting frameworks by

- reminding ourselves why we set goals for our organization

- being precise about what constitutes great goals, og how they are similar and different around the organization

- showing how you can create an aligned Goal Map for the entire organization and

- Illustrating how to iterate around the Goal Map to keep the strategy relevant at all times

Compared to the frameworks that have historically dominated, I will claim that if you follow this article, you can

- work with goals the same way across the entire organization, both in relation to formulation and measurements, for clarity and transparency

- ensure the goals are aligned top-down and across to the benefit of everyone, and

- set up processes to continuously strategize and align the organization

I do not claim that this is an easy fix. On the contrary, creating effective strategies across the organization and ensuring that the organization collectively implements the most important parts is difficult, requiring a lot of time, alignment, and persistence.

My advice regarding mentally taking on the task is to think about it as an incremental process that does not restart every December, but as something that is maintained continuously following changes in the market, by competitors, in technology, etc.

Every iteration is manageable for everyone to complete and comprehensible for everyone to understand the changes, as it is updated frequently.

I may have covered too much ground here. If something is unclear to you, do not hesitate to make contact.

- https://rework.withgoogle.com/intl/en/guides/set-goals-with-okrs original: Andrew S. Grove (1983). High Output Management.

- Robert Kaplan and David Norton (1996): The Balanced Score Card

- Peter Drucker : Management By Objectives, 1954

- Richard Rumelt : Good strategy Bad strategy (2011)

- http://www.managecomplexity.dk/blog/2019/05/23/agile-planning-circles/

- Daniel H Pink: Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us (2011)

- George T. Doran, “There’s a S.M.A.R.T. Way to Write Management’s Goals and Objectives.” Management Review November 1981

- Eric Ries: The Lean Startup (2011)

- Jim Collins and Jerry Porras (1994): Built to Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies.

- Chris McChesney, Sean Covey, and Jim Huling (2012): The 4 Disciplines of Execution (4DX)

- https://www.slideshare.net/dmc500hats/startup-metrics-for-pirates-long-version

- http://www.managecomplexity.dk/blog/2025/08/25/get-your-development-teams-right/

- http://www.managecomplexity.dk/blog/2025/08/25/what-team-topologies-becomes-with-a-user-rather-than-systems-focus/

- http://www.managecomplexity.dk/blog/2020/05/12/strategizing-over-strategy/

- http://www.managecomplexity.dk/blog/2025/03/05/your-glass-floor-is-their-glass-ceiling/