I recently wrote an article1 about a way to consistently decompose your development organization into user-focused teams to optimize value creation. Despite numerous previous attempts, I felt that no one had adequately addressed how to achieve this, even though there is general agreement that most teams should be product or stream-aligned, at a ratio of 6:1 to 9:1 compared to other team types. If you’re also frustrated by the lack of guidance on how to decompose your organization, I suggest you read my first article on this topic.

While I wrote that article, I realized that I had more to contribute to the, in many ways, a great book on team topologies by Skelton & Pais (S&P)2, as well as other work in this area.

In this article, I’ll share experiences that can clarify and extend the understanding of enabling, platform, and complicated-subsystem teams.

In my experience, achieving the recommended ratio of product teams in established IT organizations is quite challenging. As a result, it’s difficult to deliver the level of value to users that would be possible with a complete shift towards a user-first mindset.

The major obstacles lie in the existing IT architecture, which cannot be changed instantly. Therefore, much of what I will share is designed to guide you through a gradual process where a greater portion of the development effort is directed toward the users.

In the first article, I referenced Conway’s law:

“Any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization’s communication structure.”3

To explain why we are likely to define our teams to reflect the existing IT architecture, it follows that to change our focus on users, we must also change the communication structures, namely, the teams and their relation to users.

To emphasize user value, I also refined the definition of what S&P refers to as stream-aligned teams. In this definition, I emphasize the importance of value creation for users to avoid ineffective team splits that cannot deliver on a clear value proposition.

| An optimal development team should be designed to fullfill some specific needs for a specific user type. It has this responibility over a longer horizon to learn the user’s needs, collaborate with each others and stakeholders, and master the technology used. |

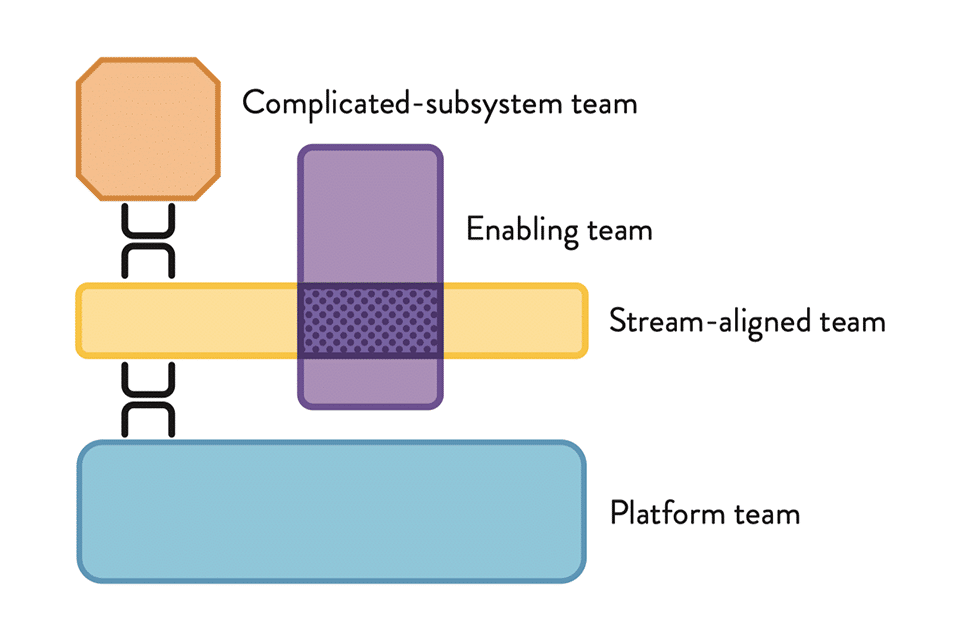

This, you may call it, obsession with creating value for users is also reflected in the following chapters on the remaining three team types that S&P has defined for us: enabling teams, platform teams, and complicated-subsystem teams.

Enabling teams

“An enabling team is composed of specialists in a given technical (or product) domain, and they help bridge this capability gap… This allows the stream-aligned team the time to acquire and evolve capabilities without having to invest the associated effort”

S&P are focused on technical capabilities, which nowadays could include AI. However, I’ve also seen enabling teams utilized when transforming work processes, such as transitioning to Agile, enhancing user interaction, and so on.

This seems rather intuitive: building these new capabilities is entrusted to a group of specialists throughout this process. The aim is for the new capability to integrate seamlessly into the daily routine of the development team, and as the organization evolves, the enabling teams will become unnecessary.

Where I have seen several organizations struggle is when it comes to the expertise that teams occasionally need; hence, it does not make sense to incorporate it into the team’s skillset. Traditionally, this has been managed by shared specialist functions, such as security, legal, compliance, HR, and finance, which I’ll refer to as centers of excellence (CoE).

The CoEs are responsible for compliance within their areas, and historically they often enforce this through default part-time allocations to projects. Since there are few specialists in CoEs and many projects, the timing is usually off, causing the CoEs to become obstacles to progress.

If central planning cannot resolve the mismatch between specialists and project teams, how should autonomous development teams allocate specialists on short notice?

One solution I’ve seen being successfully implemented is to reverse the responsibility; that is, the teams have the responsibility to comply with corporate rules. To take on this responsibility without wasting a lot of time copying CoE expertise into the team for rare use, three demands were placed on the CoEs:

- They were obligated to make them known to the team:

- arrange an introductory meeting where they

- present their offerings and situations where the team is expected to contact them, e.g., as a poster, checklist, or contacts.

- return when they have updates, e.g new offerings to the teams

- They should always have time for an hour-long consultation on very short notice to provide advice on smaller challenges and agree on how to collaborate on larger challenges. For example, they could reserve one hour every day in the calendar where teams can just show up; if no one shows, then they can do something else.

- When teams need greater involvement from a CoE, the CoE flows to work. This means that a member of the CoE becomes a temporary team member, sitting with the team during a period of knowledge transfer, so the team can be more independent the next time a similar challenge arises.

To ensure that the CoEs do not become a blocker for the team’s progress, there is an additional rule: a CoE can never delay a team’s work. If a CoE does not have time to engage, the team is allowed to make decisions independently, as long as they keep the CoE informed of their actions.

If that situation occurs too frequently, it indicates that the CoE is understaffed. If nobody seeks advice from the CoE, it may be overstaffed, or it has not effectively communicated to teams when they need to consult them. The latter can, of course, have significant consequences.

On the boundary between Enabling and Platform teams

Above, I aim to limit the definition of the enabling team type to those who infuse knowledge into the broader team, rather than a specific role within the team.

I believe it makes it simpler to discuss what S&P calls tooling teams, without being one of their four basic team types. The reason for this is several organizational constructs can support that tooling.

Before discussing the implementation, I’d like to shift the perspective from tools and technologies to how users are supported in creating the value they need to deliver. This is no surprise to those who have read the article I mentioned earlier, so I’ll just reiterate that more value comes from considering the users’ perspective.

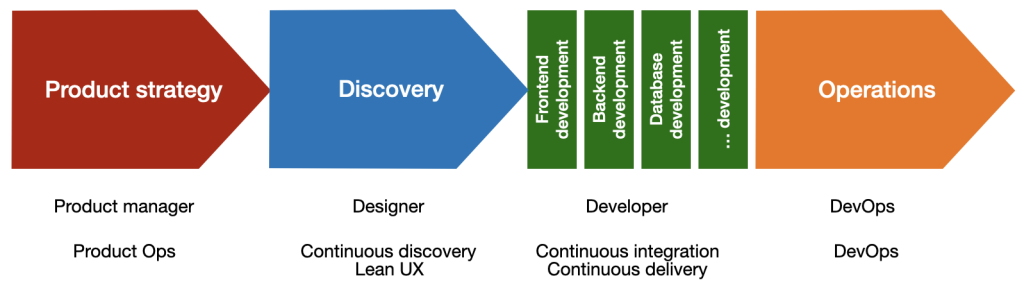

The users here represent the roles within the team: product manager, designer, developers, and operations, and the value stream is the development value stream illustrated at a high level below:

Further details on the separate parts of the development value stream are discussed elsewhere, such as ProductOps, Lean UX, Continuous Delivery (CD), and DevOps4. Therefore, I won’t delve deeper into this here, but rather stick to the general discussion.

Sharing methods, tools, artifacts, and other resources among members of different teams is beneficial, as S&P focuses on reducing cognitive load for individual team members, allowing them to concentrate on product development and thus increasing productivity.

Furthermore, it is essential to create a cohesive solution for users that functions across products from various teams.

Despite the value of investing in the productivity of individual developers, we must remember that this money cannot simultaneously be used to build for the users who actually pay for the product. Therefore, the amount invested must be balanced. Another crucial topic to consider is that when you remove the choice of tools from developers and centralize it within a team, you may also lose accountability.5

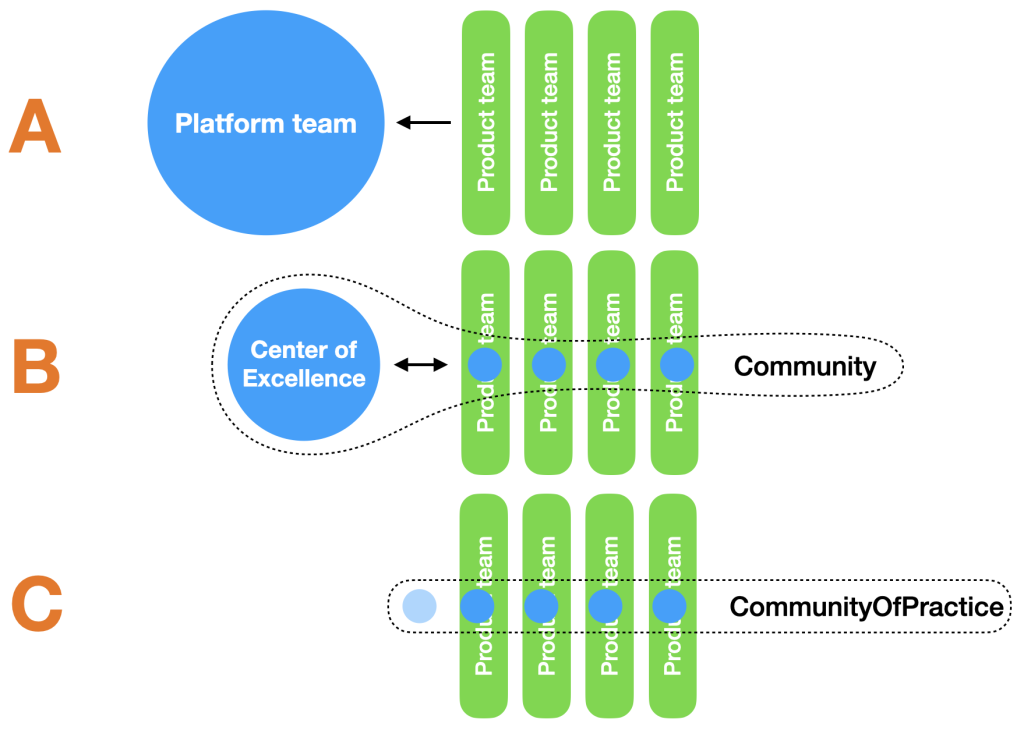

I believe there are essentially three distinct organizational structures that can address the requirements for standardized cognitive offloading methods, tools, and other related needs.

- a platform team, which essentially is a development team focused on the development value stream, that decides and builds shared support for a role in the teams, such as coding standards and the CD pipeline.

- a Center of Excellence (CoE), which is essentially a smaller enabling team that helps team members do things right in their context, or

- A Community of Practice where team members in a specific role meet, for example, weekly, to learn from one another and collectively decide on the standards they should adhere to and which tools they will share to ensure their work is consistent and effective.

A figure like the one above greatly supports the discussions that lead to decisions on how to organize in the moment and what your expectations are for changes over time.

If your organization is new to a discipline, e.g., wants to implement Continuous Delivery for the first time, it is a significant task to establish development practices and infrastructure to support that. It would be beneficial to form one or more teams that can dedicate themselves fully to reaching a point where product teams do not have to be overly concerned about Continuous Delivery.

However, if your tech stack is quite heterogeneous, the number of platform teams increases. If you make the same decision about support for other roles in the teams, you’ll end up with too many non-business-oriented teams. Remember, the rule of thumb is a 6:1 to 9:1 ratio of product teams to the total number of other teams, ensuring that the focus remains where it should be: on the user who ultimately pays for your work.

A smaller initial investment or a step to descale the platform team would be a CoE (as described above) of a few specialists who help to get the support built into the teams. Although progress may seem slower, you will benefit from greater learning and accountability among team members in utilizing and extending the common support.

A further step toward ownership and accountability is to assign full responsibility to those developers who use the platform daily by organizing them into a Community of Practice (CoP). I’ve written about running CoPs in two other articles6,7, and provided an example of how a CoP sometimes resolves platform issues that central organs cannot. Worth repeating here is that succeeding with this requires excellent leadership, no matter if it’s a Product Manager for a team or a leader of a CoP.

There is no right or wrong here. It should evolve over time, based on the platform’s maturity or the necessity for a significant shift, such as transitioning from proprietary servers to cloud infrastructure. In my experience, the best approach is rarely to maintain the same organizational structure for every part of the development value stream.

A Warning on Platform Teams

From the above, you probably sense that I am not the biggest fan of the term “Platform teams.” Not because it is not an accurate description of what they are, but because I see them as temporary, to be replaced by CoEs and CoPs. Additionally, they do not exist to build a platform, as most of us with a technical background interpret from the wording.

Their job is to support business-oriented teams in any way to enhance productivity, reduce cognitive load, and ensure that users have a coherent experience regardless of which product team has developed what the user utilizes.

Therefore, I recommend that platform teams, to a large degree, be defined and operate in the same way as development teams, with clearly defined responsibilities in the form of a particular user and part of a value stream. The difference is that the users are developers of different kinds, and the value stream is the development value stream, as illustrated above.

It may take some effort to ensure that platform teams, which usually consist of very capable technical people, adopt this perspective, but in my experience, it is worthwhile to achieve that.

Complicated-subsystem teams

The final S&P team type is the complicated-subsystem teams, which are known in other terminologies as component teams.

Some of the examples they provide are video processing codec, a real-time trade reconciliation algorithm, a transaction reporting system for financial services, or a face-recognition engine. I disagree that these belong in this category because, in my understanding, they are value-creating steps for users. For instance, when they watch a video, reconcile trades, report, or log in to a system, these steps play a crucial role for users. Of course, they are complicated, may require significant capacity, and might seem insignificant to users; however, without them, users could not complete their tasks. Therefore, these are teams like any other that collaborate with other product teams to meet the needs of users along the value stream.

The other category is the large monolithic system that you’ve either built yourself or purchased to manage functions like billing or CRM. However, it requires separate attention, because in my experience, these systems cause a lot of trouble for a large majority of product teams.

S&P mentions multiple types of monoliths and multiple fracture planes, i.e., ways to split the monolith. Throughout the article, I have argued for optimizing value creation for users, so decomposing complicated subsystems along the last one they mention: “user persona” is my preference, i.e., creating product teams similar to the definition early in the article.

In the rare event that you’ve identified a single system (e.g., SAP for manufacturing companies) capable of supporting all your different users without significant adaptations, it makes sense to let the structure of the monolith dictate your teams. However, if your users rely on multiple systems to perform their work or if certain work processes are inadequately supported, it may be beneficial to consider product teams that manage parts of the monolith(s) to generate value for your users.

What makes such a decomposition challenging in monolithic complicated subsystems is that working with them requires extensive knowledge about, for example, entire data models, configuration frameworks, business logic, etc. The individuals who master this expertise are typically few, meaning they cannot be part of every team. As a result, a longer transition period is to be expected.

The goal of the transition period is to increasingly decouple product teams from their dependencies on the complicated subsystem.

The first step is to shift the responsibilities of the complicated-subsystem team from merely serving as order-takers for everything required in the system to functioning more like a platform team. This team will gradually expose more functionality to the product teams, enabling them to integrate, configure, and extend the complicated-subsystem independently. The ultimate goal is to achieve independence from knowledge of the subsystem.

That goal will (almost by definition) never be reached for all users of the really complicated subsystems, so you’ll need to prioritize the value creation for different users in order to decide the sequence of the transition.

In my experience the order is defined by multiple things:

- If you have users whose problem-solving spans multiple systems, you will create the most value by decoupling them first. An obvious example is banking customers’ self-service.

- If you have systems that you prefer not to touch much any longer because of lack of people who can maintain them, aged technology, redundancy, etc.

- If you want to substitute part of the system, either certain functionalities need to be replaced by another system or component, or a layer of the system, such as the user interface, may need to be changed.

etc.

Unless you have unlimited funding, I recommend approaching this transition with awareness of the above and accepting that the boundaries will always be fluid. You’ll encounter everything from product teams that can fully support their users within the system to teams that can accomplish all their needs through APIs to these systems, initially developed by a complex subsystem/platform team.

Due to these dynamics, it is important to understand the various team types, their interactions, and how to implement transformations.

Conclusions

If this article appears overly critical of S&P, it has certainly not been my intention. My extensive experience working with team topologies in large organizations has taught me several valuable lessons that I would like to contribute to their great work.

Most importantly, to maximize value creation, aim for a ratio of 6:1 to 9:1 of product teams to other team types. Always remember this when tempted to focus on internal technical complexities, allowing them to dictate your team decomposition. This is rarely the path forward.

The optimal team topology is unique to each organization and, likewise, is the path toward better serving your users. This journey will be challenging, especially if your current systems are designed by a technically oriented organization. We know this from Conway’s law.

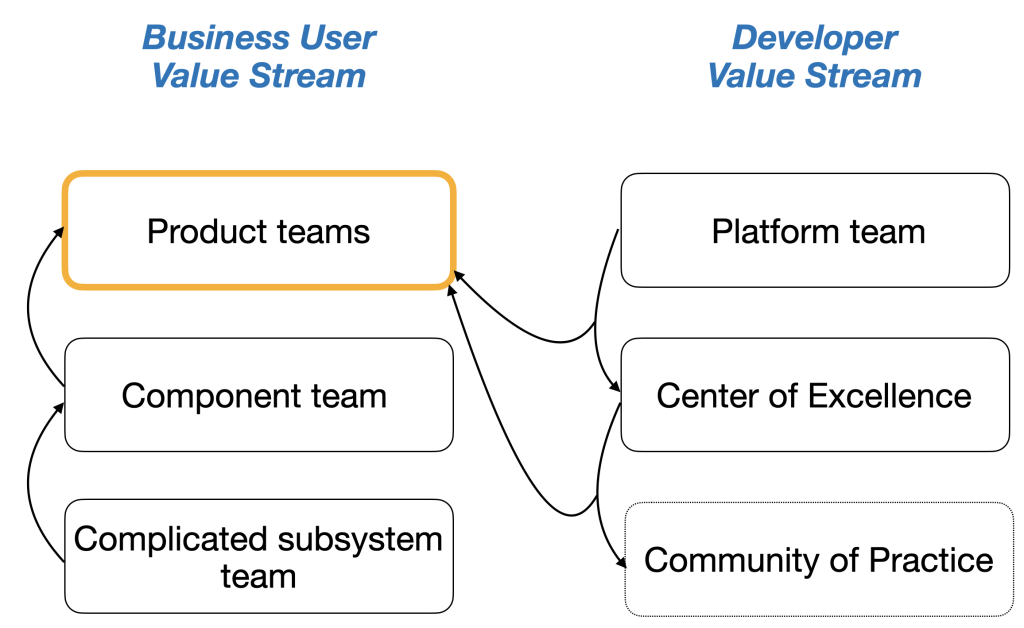

I’ve created the illustration below to illustrate paths for maximizing business-oriented development teams. In short:

- Maximize for teams aligned to the business users’ value stream.

- Migrate development teams that are detached from direct user contact to become product teams.

- Migrate platform capacity to CoE and CoP and integrate capacity into product teams..

Whether you need to get a good start on your journey or you require cheering up or assistance when Conway shows his teeth, feel free to contact me. I’ve tried it before.

- http://www.managecomplexity.dk/blog/2025/08/25/get-your-development-teams-right/

- https://teamtopologies.com

- https://www.melconway.com/Home/Conways_Law.html

- for example: Melissa Perri : Product Operations, Jeff Gothelf : Lean UX, Teresa Torres : Continuous Discovery Habits, Nicole Forsgren : Accelerate

- http://www.managecomplexity.dk/blog/2025/03/05/organizational-accountability-with-highly-autonomous-teams/

- http://www.managecomplexity.dk/blog/2025/03/05/your-glass-floor-is-their-glass-ceiling/

- http://www.managecomplexity.dk/blog/2025/03/05/organizational-accountability-with-highly-autonomous-teams/