In product development, we have learned that autonomous cross-functional teams focusing on users create the most value. The methods we use have undergone significant development over the last three decades, and it is well described how a single team should work to achieve great results; however, it has proven not to be easy or straightforward. On the contrary, many organizations are struggling to maximize value creation. Especially at scale, where many teams work on the same offerings, previous approaches have proved insufficient.

In this article, I will share how a different perspective on team structure design can overcome the typical barriers to optimizing value creation through the right team topology.

I will

- challenge your beliefs on how your development organization creates most value for you and your customers.

- teach you how to design a team structure optimized for value creation,

- possibly also surprise you how this approach also simplifies the way the organization works.

Previous approaches

When the organizations are large, it is well-known that the efficiency of each team suffers from coordination, dependencies, redundancies, etc. and therefore several different approaches have been taken to improve upon this:

- In the 2010s, Agile scaling frameworks1 tried to improve it by defining how these teams should collaborate

- In 2019, Skelton & Pais2 gave us a vocabulary to design our team topology and a rule of thumb: the ratio of stream-aligned teams (those that create value for users) to other types of teams should be between 6:1 and 9:1.

- Jürgen Appelo tried to do the same with his UNFIX model3, as well as Mik Kersten in “Project to Product.”4

These approaches focused on optimizing development output, i.e., the amount of functionality the team delivers. These approaches all focus on optimizing flow in the development process at scale. In other words, the Agile software movement has, until recently, focused on the developer value stream and optimizing flow to get as much (code/features) out as possible.

From the late 2010s, many product-management-oriented individuals, such as Marty Cagan5 and Melissa Perri6, inspired by agile software development, have advocated for product teams that, in structure, resemble those mentioned before but with focus on the user outcome/business impact the team creates. However, the term ‘product’ is very confusing, especially in large organizations, where many teams contribute to one product as perceived by the customer. Therefore, I will not use this term despite it being the buzzword in recent years.

I believe that each of the above, despite valuable inputs, fails to help organizations with the central challenge of decomposing their offerings into parts for autonomous cross-functional teams. Collaboration is essential but not sufficient; a general description of stream-aligned teams (Skelton&Pais) does not help a specific organization to identify the best team structure, and many organizations cannot see their complex offerings decomposed into sizes that fit individual development teams.

In this article, I’ll attempt to explain how you can decompose your offerings into smaller products that can be handled by a single team or a very few teams. I’ll also explain the advantages of doing so in more depth.

What is an optimal development team?

The teams we’re aiming for are referred to by many different names (agile, stream-aligned, product teams). I do not think that any of the names capture the multiple dimensions of requirements for teams, so to avoid confusion with the terminology of the approaches mentioned above, I’ll simply call these (optimal) development teams.

A prerequisite for being an optimal development team is the team conditions that have been repeated again and again for almost 30 years7. An optimal team must be:

- small ie, 3-9 members,

- cross-functional, i.e., can deliver the whole value independently,

- members are 100% allocated to the team

- stable, i.e., together for years and

- co-located (perhaps becoming less important due to our practicing remote work during COVID)

This helps to maximize the development flow. Furthermore, we have learned8 that the team should

- release often/continuously to real users and

- gather instant feedback from users to deliver optimal business value and quality over time.

The fact is that these teams deliver more and more value as they learn

- to understand the users and their needs

- to collaborate with other teams and stakeholders,

- to master the technology,

- etc.

To accommodate these constraints, I have realized that there are a couple of very important design criteria for teams that the previous approaches have not emphasized the importance of:

| An optimal development team should be designed to fullfill some specific needs for a specific user type. It has this responibility over a longer horizon to learn the user’s needs, collaborate with each others and stakeholders, and master the technology used. |

You should notice three things:

- The team is measured by the value (outcome) it creates for users rather than how much it builds (output). This may seem like a subtle difference, as we often assume that the more we deliver, the more value we create. Research by Standish Group9 and Google/Booking/Netflix/Amazon10 has shown that this is far from true: two-thirds or more of the features we develop have no or even negative value.

- The team’s proximity to users allows them to gain intimate insights into their needs, and hence, create better-fitting solutions. Focusing on users and their needs also has the advantage that it can be easily expressed as changes in their behavior, which is easily measurable in modern systems. This will give early proof that we’re achieving what we want. I will unfold this in a later article.

- This is a much stricter definition than previous attempts like Skelton & Pais have given us:

“A stream-aligned team is a team aligned to a single, valuable stream of work; this might be a single product or service, a single set of features, a single user journey, or a single user persona.”

When it comes to their examples, it becomes clear that a stream can be any type of work, and the measure of success is the output. Their examples come from a quite technical point of view based on how to split a technical monolith along possible fracture planes in the system. They also see the change frequency of different parts of the system, risk, performance, regulatory compliance, and technology as natural separations between stream-aligned teams.

This leads to an organization designed from the inside out, focusing on random system capabilities instead of the user perspective, from which value creation flows. Adding their platform and complicated sub-system team types, it is apparent that they design the team topology from inside the IT department and out. It is, of course, a valid way to approach the complexity of designing teams.

Here I will, however, insist on the user value perspective, because current and future revenue comes from solving the users’ problems, so they are willing to pay for your products and services.

It is a break with years of tradition of IT-departments as a deliverer to the business, which has formed organizations:

- primarily organized in departments with people who master the same skills and focus on specializing in those

- develop through larger temporary projects across these departments with a focus on delivering functionality as fast as possible

- purchase standard systems and integrate out of the belief that they get more and better standard functionality

According to Conway’s law, systems and communication structures reflect each other:

“Any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization’s communication structure.”11

Therefore, what Skelton & Pais suggest is a better fit for the existing IT architecture, but it also follows from the rule that to change our focus from IT-architecture to users’ needs, we must also change the communication structures, i.e., the teams and how they engage with users.

It will make this article as challenging as it is rewarding.

Having established that optimal development teams should be defined by their user type and their needs to create optimal value, we still need to understand how to meet the ‘long horizon’ criteria.

Stability gives responsiveness

Even if you have seen how teams struggle with dependencies, etc, at scale and wish to harvest the benefits of optimal development teams, I have experienced that there are two major assumptions behind traditional development organizations that have to be challenged before moving on:

- Everything changes all the time

- Responsiveness to change comes from frequently changing organizational structure

You may well argue that there is an everlasting flow of challenges from customers, technology, regulators, subcontractors, geopolitics, etc., so it does not make sense to challenge this.

However, the perception that there is a conflict between stable teams and the shifting challenges the business meets may be nonexistent for two reasons:

- the business is much more stable than we perceive

- shifting organization often lowers our ability to respond to challenges

These claims challenge the assumptions behind how we’ve organized ourselves around temporary projects, so I’d better explain this more deeply. Remember that I’m here, focusing on larger organizations that struggle to get their teams right. This does not apply to startups or scale-ups to the same degree.

Your business is much more stable than you perceive

When you’re a senior executive or business developer, your perspective is to respond to challenges. But try to switch perspective to that of your users and the value you provide them through your products – the products you are so focused on changing to meet challenges. How much has that changed since the company found a product-market fit and became successful?

At first thought, you’ll probably say a lot, but let me give you a few examples from a couple of the organizations I’ve worked with on this topic:

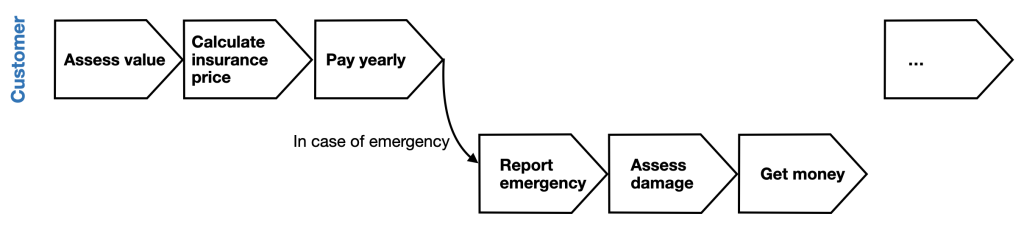

A 250-year-old insurance company provides the same fundamental value to customers: restoring their value in the event of an emergency. Also, the user value stream has been more or less stable during the 2,5 centuries: access value, calculate insurance price, pay frequently, report emergency: access damage, get money… :

Needless to say, technology has changed the support of the value stream many times during that period. Latest AI is (partly) replacing customer service, but as an organization, it is crucial from this perspective that the value for the users is the same: faster and more precise help.

For years, a 50-year-old software company has built a software platform for investment firms, supporting numerous user types, including performance managers, portfolio managers, and accountants, throughout the entire investment value stream. Again, the user value streams have, in essence, remained stable throughout those years, dating back to long before the software company began supporting them. In this case, it is so stable that when looking at, e.g., smaller niche competitors, it is easy to map them to specific parts of the user value streams and make comparisons to parts of the platform and compete both in the niche and on the total solution.

If you’re in a mature organization, try to single out the main users and the primary value that historically made them use your product. My assumption is that you’ll recognize the above-described stability and that growing your product has been to support more of the value stream or similar value to its users. In the examples above, the insurance company attempted to add additional financial products over time, while the software company expanded from supporting investment accounting to encompassing the entire value stream.

Shifting the organization is confused with responsiveness to change

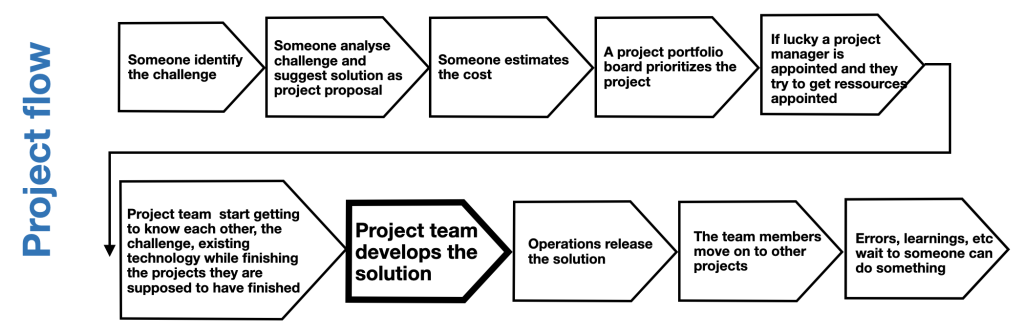

The other misperception about stable teams is, as mentioned that stability should lead to slow response to challenges. To convince yourself that it is not true, consider how organizations typically respond to business challenges. In many organizations, it goes more or less like this:

I’ll accept the argument that if some change is really important, we can react much faster than that, but if you think of your average business initiative, it is my experience that a large majority of larger project-driven organizations recognize that it can take year(s) before we can harvest the value of the initiative.

Notice that only one arrow (the fat one) is actually building the solution; the remaining arrows represent analysis, decision-making, and being ready to build and release to users. That is switching time, which shows how unresponsive we are to challenges.

Furthermore, many learnings are lost because those who were involved in the projects have moved on when learnings could be harvested, i.e., while users are using what was made. These learnings about the business problem, technology, etc., are essential if you want to respond fast.

Long response time and low learning are minimized by stable teams because they can reprioritize very fast (typically a couple of weeks) and remain in the learning loop with the users.

We’ll actually increase our strategic agility by having quite a stable organization that is prepared to react to whatever comes at us, compared to taking the cost of rebuilding the organization with every change.

Now that I’ve argued for long-lived teams aligned to user value streams, let’s see how it is practically attainable.

Decomposing the organization into optimal development teams

By now, you have probably figured out that the focus when identifying optimal development teams is the users and our overall value proposition to them, rather than the changes to our systems. I have split the process into six steps:

- Identify your primary users

- Visualize the user value streams

- Apply your strategy

- The Product Managers take over

- Handle dependencies

- Handle new strategic priorities

The first steps in decomposing the development organization are to visualize the user value streams, i.e., the flows of value we provide to our users from their perspective.

There are alternative value streams that you could look at when decomposing your development organization into teams, and below I’ve listed some of those that people has asked me about and why they are less usable:

| User Journey | Typically, focus on the interactions with users, and you may therefore miss the user value that is created behind the scenes by employees or is automated |

| Customer Value Stream | In B2B solutions customers and users are not the same and furthermore development teams can only influence users Teams also serve for example internal users and handling any kind of user the same way simplifies what you try to achieve |

| Operational Value Stream | Is typically an inside-out perspective which you cover by looking at both external and internal users |

| Development Value Stream | Development team members are users in the development value stream so you can actually understand platform and enabling teams (Skelton & Pais terminology) the same way as business users just on a different user value streams (much more in part 2 of this article) 12 |

I’ve been working with several very large organizations around this. I was tempted to use one of these as the example throughout, but I realized that details from these examples may be hard for readers not related to those businesses to relate to. Therefore, I use a practical example that most people can relate to: an e-commerce business at scale.

Step 1: Identify your primary users

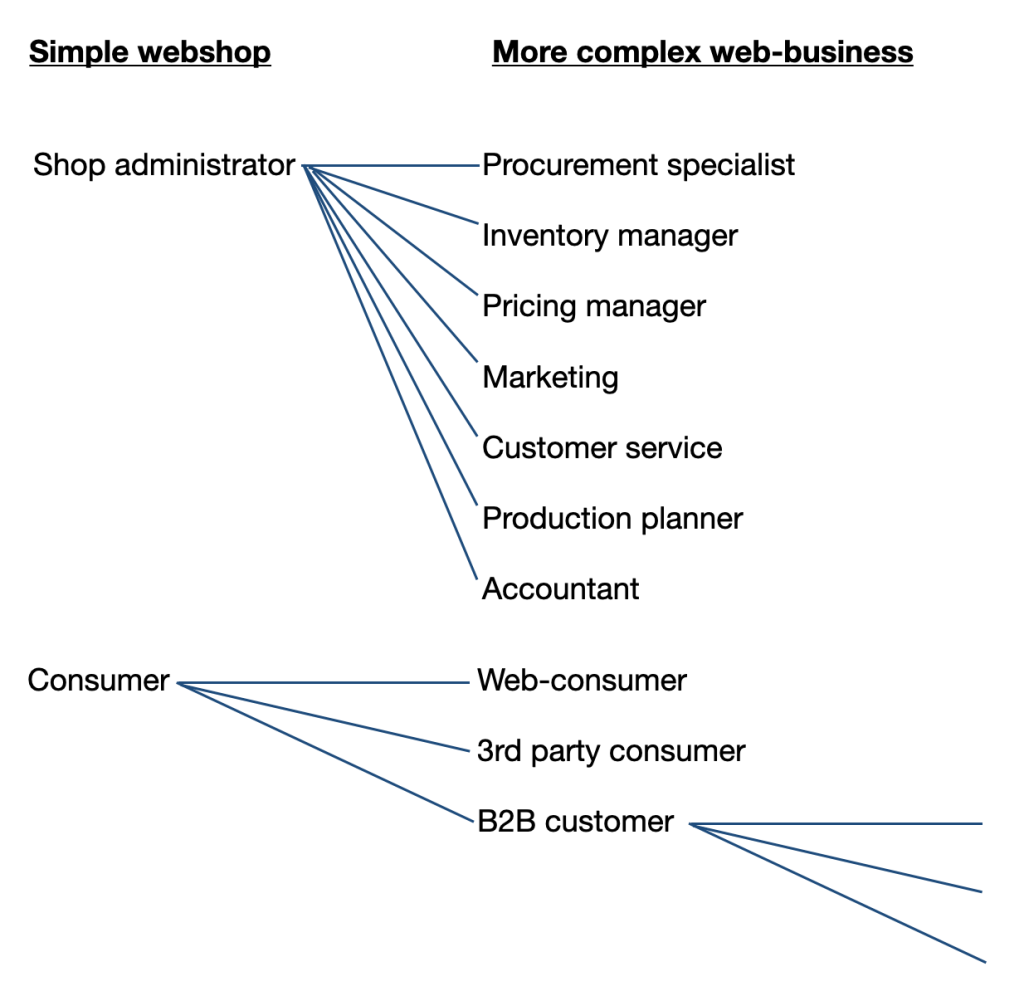

If your teams are building a simple e-commerce solution, you may only need to be concerned with two user types: the consumers and the shop administrators. However, as you become successful, you’ll support more work with your system:

- procurement for resale becomes increasingly complex with the number of products and suppliers

- inventory management and marketing, likewise

- having the best prices becomes more essential, and you might choose to produce your own products to increase your margin

etc

- You may also establish additional channels, such as third-party portals like Amazon or trade B2B with other shops.

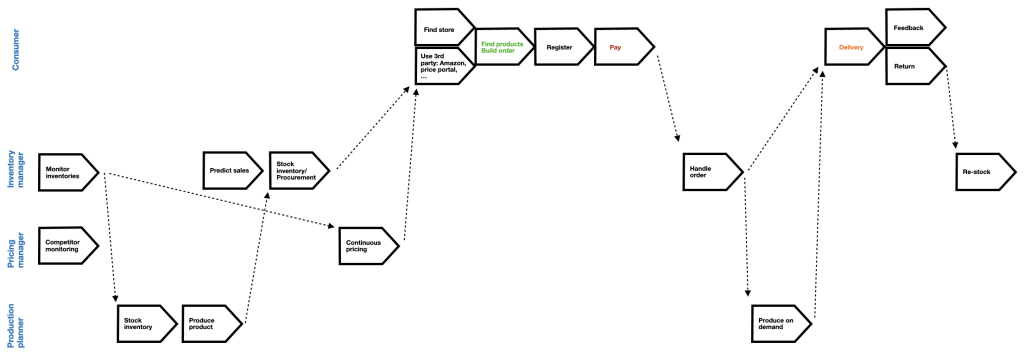

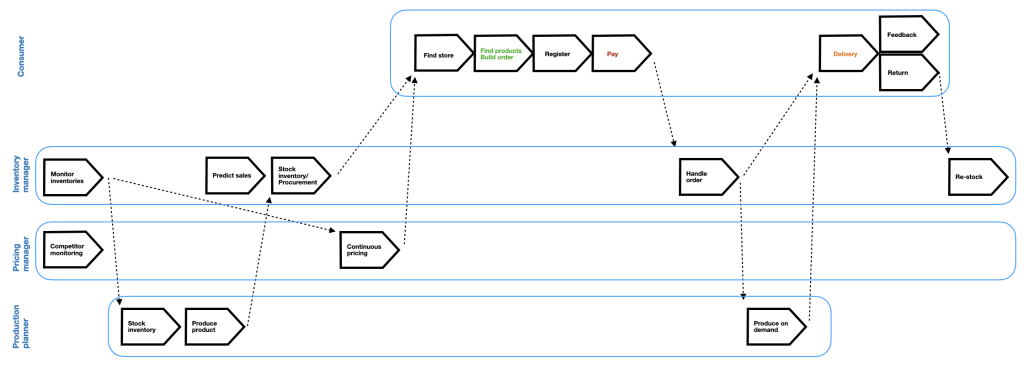

The more you grow, the more you want to automate, and your teams have to build for more user types (see the figure to the right).

The relevant user types depend on the business you run, and it is essential to know them intimately when you want to organize your development effort in teams and reap the benefits. Identifying as many user types as possible in this step and adding diverging user types as you identify them through the following steps will help to make your value creation more explicit. For example, entering the B2B market will likely reveal more user types as you integrate into their value streams.

Step 2: Visualize the user value streams

After identifying the user types that you support as a development organization, you should map out the users’ value streams, i.e., how they obtain value through their actions.

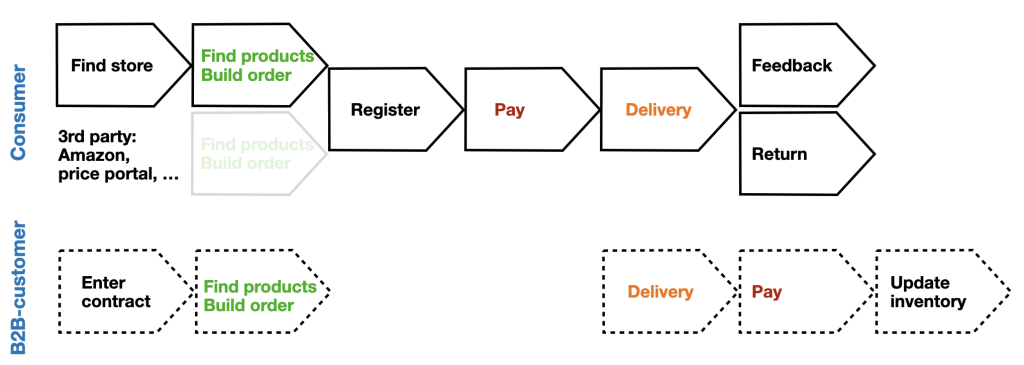

The value streams of the e-commerce example are illustrated below. For the consumer, the value stream begins with selecting the store, i.e., through a commercial, a search, a portal, or as a returning customer. From there, it continues like any other web shop, you know. The value-creating steps are largely the same, despite being implemented in different ways.

When examining the B2B customer, the steps are generally the same: build order, pay, delivery, etc.

From an efficiency or IT-architecture perspective, it would be tempting to conclude that we need an order engine, a payment system, etc., that can be reused across different users. Surely, software vendors will confirm that buying their systems will get you up and running fast with a cheap project.

If your perspective, however, is to support your users in creating as much value in their work as possible, and in doing so, they are more inclined to purchase from you, you must take their perspective.

Doing so, you’ll probably soon conclude that the B2B Customer is not a user but rather multiple different users. The person who orders your products may be a store manager, a central inventory manager, or both. They may be able to do it through an interface that you provide, or they may prefer to integrate their inventory system into the purchasing process.

Payment may be processed through accounting, and one order may need to be delivered to multiple locations via different logistics partners, which may or may not be handled by a different user at the B2B Customer. To serve these users so they prefer your solution, you should map out the value streams for these user types, despite the fact that they may vary from customer to customer.

These examples illustrate why you should exercise caution when concluding that a team is necessary to handle cross-cutting concerns, rather than aligning with user value streams. Payment, etc., could be a component (or system you buy) shared among the development teams that are optimizing sales for specific user types.

Let’s leave that for now and continue with some of the internal users mentioned above.

The simple version of the inventory manager’s value stream involves monitoring, stocking, and picking from inventories. Sales prediction and procurement may be separate users, but we’ll consolidate this into a single value stream for simplicity.

Similarly, the simple version of a pricing manager and the production manager of our products are illustrated below.

If these value streams were completely independent, it would be easy to let different teams focus on each particular user, but they are typically not, as illustrated by the dotted dependency arrows above. To take one example: From monitoring the inventory, we identify the products that should be emptied from the shelves, which is used as input to the pricing manager to determine the discounts that are presented to the customers through different channels.

Identifying dependencies is important because they inform decisions about what responsibilities teams should be given to minimize dependencies and provide transparency about what other teams they need to collaborate with. More about this later.

It is evident that there are more external users, such as suppliers of products or materials for production at one end and delivery services at the other, and more dependencies; however, the above is sufficient to illustrate the principles.

In this context, we conduct this exercise to define the optimal development teams. However, in my experience, understanding all user value streams across an organization helps facilitate many dialogues, from the strategic level to daily collaboration.

Step 3: Apply your strategy

Another thing that the value streams help to realize is that, drawn in full, they constitute your whole business, which you have to support going forward. Once you have chosen to support a user’s value creation, it is a commitment that lasts until you close that part of your business13. You might not want to invest a lot in that part. Still, there will always be maintenance required following changes in the underlying technology, changes in other parts of the business with dependencies, new regulations, and so on.

This is where applying your strategy comes in. Every value-creating step must be owned by a team, but the number of value-creating steps a team can handle depends on the strategic investments in the part of the business in question.

For simplicity, let’s say that our business has four different focuses: Building the customer experience, optimizing inventory, pricing, and production. Fortunately, that fits with our four primary users, which makes it easy to map focuses to teams. Each circle below illustrates the responsibility of one team.

In terms of development, each circle represents a product, hence defined as:

| A product is defined by a user and (part of) its user value stream, and is managed by a Product Manager and one (or a very few) optimal development teams. (At scale, a product from the customer’s perspective consists of several products) |

Each product is assigned a Product Manager (PM) who has the long-term responsibility for the direction of the product, i.e., the product strategy. For example:

- the ‘customer’ PM has the strategic responsibility to build what improves the customer’s experience and increases sales

- the ‘inventory’ PM has the strategic responsibility to build what ensures cost-effective inventories that, at the same time, live up to the promises to the customers

Step 4: The Product Managers take over

Having the value stream map with team responsibilities makes it clear to every PM what their responsibilities are in creating which value for which user(s), as well as the responsibility of all the other PMs. Together, that covers all the business.

After a PM has been empowered with a defined user, (part of a) value stream and team(s), it is their responsibility to present and maintain a transparent product strategy consisting of, for example, vision, roadmap, competitor analysis, etc., and to align with other PMs—especially those with dependencies in the value stream maps.

The PMs should maintain continuous dialogue around their strategies and future roadmaps to ensure they align, incorporate their input into corporate strategy, and execute decisions.

In my experience, executing new changes in existing teams is definitely possible and faster because

- the initiatives come from a continuous strategizing process around the team, so they adapt their plans and capacity accordingly. Suppose you decide to grow a specific value stream long term. In that case, you can let the team grow organically until it is beneficial to split it into two, who both refer to the same PM

- you save the cost of starting a project of people who are not used to collaborate around a business area they do not know intimately while bringing instability into the teams they come from.

Of course, growing and shrinking teams according to future plans for the value streams is not always sufficient, but try to think about how often you have changed the fundamental value streams. My guess is that a large part of the projects you have historically started operate within existing value streams, but are used to secure the capacity to create change.

It is now obvious that a PM is a crucial leadership position, as they bear a significant responsibility for the business. They must be competent in product management to fulfill the role and gain the trust of the organization, which secures their decision-making power.

Despite being both capable in product and organization, it is essential to ensure that new silos are not formed around the PMs. They work for the benefit of the entire organization and are required to collaborate with other PMs and senior leadership to develop the business as a whole.

Step 5: Handle dependencies

The value stream maps can be shared in the organization for widespread collaboration.

As mentioned, the PM uses it to understand who they need to collaborate with when their strategic ambitions go beyond their own part of the value streams, both during planning and execution. For example they make sure their teams build simultaneously to optimize collaboration.

Upper management can use the map to overview current and future strategic investments, both at the corporate and product levels.

The users of the map can identify the PMs they need to share ideas, problems, etc with.

Developers frequently collaborate across teams. They can also use the value stream maps to guide them in the right direction, but since the maps do not address technology, they require additional alignment on the technical changes. Depending on the size of the technology change, they can resolve the dependency by

- bilateral dialog

- mediated by an IT-architect

- in a developers’ community of practice14

Getting into those details is outside the scope of this article. Only handling inter-PM dependencies is described further in step 6.

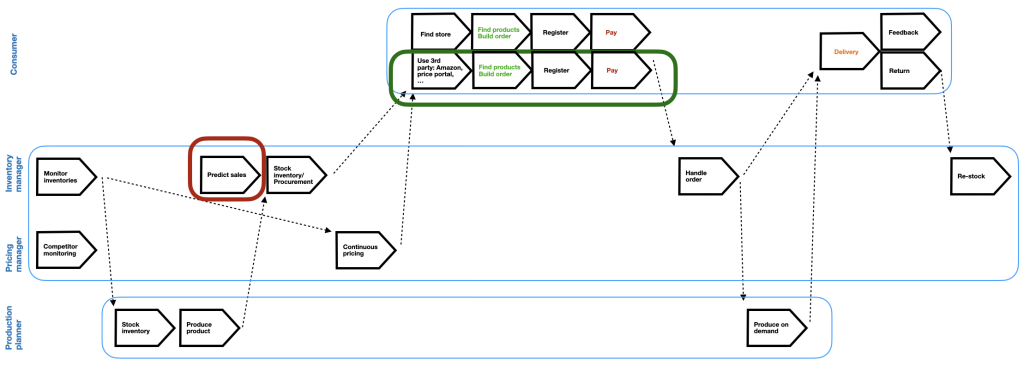

Step 6: Handle new strategic priorities

Let’s now examine how to adjust the teams when business challenges alter the priorities in the underlying value streams. To continue with our example, imagine that the customer PM can argue that the business will grow significantly if invested in long-term sales channels other than their own website, but realizes that they cannot execute on it alone. Then, it becomes a corporate decision to execute the idea and adjust the team structure accordingly.

In the example, let’s say there is money to start another team that can focus solely on sales through third parties (green circle). Preferably, the team should be a mix of experienced individuals from the old customer team and new ones, ensuring that both teams have experience with the existing solutions and are accustomed to collaborating informally with other teams.

The change also requires a significant investment in sales prediction, as volumes can fluctuate substantially. That justifies a whole team’s attention, but we cannot invest in further recruitment. Therefore, the inventory and pricing teams are brought together to form two new teams, consisting of people from both value streams: one to build the new sales prediction (red circle) that fits into the existing value streams, and one to build the combined roadmap for pricing and inventory.

Of course, the latter team will deliver the roadmap at a slower pace than before, but that is a consequence of the strategic business change and increases investments less than required. These arguments are, however, understandable for everyone in the organization, and since the team responsible has intimate insight, they can quite quickly adjust the stakeholder’s expectations to reality.

Optimal development teams at a very large scale

The foundation for trusting that the stakeholders mentioned above are proactive in fulfilling their individual responsibilities for the organization’s greater good is that they can actually navigate the organization.

The fundamental strength of value stream maps and the overlaid teams is that they change less frequently than project portfolios and that they encompass all value created within the development organization. Especially the value-creating steps are stable over the years.

This is true in the relatively simple example used here, but also for the two very complex organizations with more than 100 teams mentioned initially. And the benefits of organizing around the user value streams grow with the organization’s size because every stakeholder knows them and does not need to know about changing organization structure/project plans to succeed in their work.

In large organizations like those above, we have benefitted from creating a higher-level version of a value stream map where value-creating steps are aggregated to one or two per development team. Hence, we maintain an overview when discussing business strategies and capacity allocation, and dive into detailed value stream maps and product strategies with the PMs when necessary.

Getting started

If you want a user-oriented development organization with the benefits mentioned here, the steps outlined above are the place to start to achieve the recommended ratio of user-oriented teams to other team types, ranging from 6:1 to 9:1.

You must start by understanding the value you create for users and then define your teams with responsibility for users and (part of) their value stream as described in the first steps.

To avoid this sub-optimization, remember the advice of this article:

- stable development teams are both more effective and responsive

- the user value streams in your business are much more stable than most realize

- Conway’s law will drag you in the direction of other types of teams, eg, Component-, platform-, and complicated subsystem teams.

Happy users who have their needs regarding their work fulfilled through your products and services are your future revenue.

Not until you’ve defined these teams should you consider the need for other team types. I’ve written another article about how you can approach this15.

The six steps will help you adapt to your local context, and you’re always welcome to contact me. I would love that challenge.

- https://framework.scaledagile.com/, https://www.scrumatscale.com/, https://less.works/ etc

- https://teamtopologies.com

- https://unfix.com

- https://flowframework.org/ffc-project-to-product-book/

- www.svpg.com/books/

- melissaperri.com/book

- http://www.managecomplexity.dk/blog/2018/06/28/agile-is-organizational-re-design/

- http://www.managecomplexity.dk/blog/2024/03/12/three-decades-of-agile/

- https://www.standishgroup.com

- Stefan H Thomke : Experimentation Works

- https://www.melconway.com/Home/Conways_Law.html

- http://www.managecomplexity.dk/blog/2025/08/25/what-team-topologies-becomes-with-a-user-rather-than-systems-focus/

- http://www.managecomplexity.dk/blog/2020/02/14/vicious-cycle-of-portfolio/

- Etienne Wenger : Communities of Practice

- UPDATE WHEN RELEASED